Important Safety Information for HyperRAB® (rabies immune globulin [human])

Indication and Usage

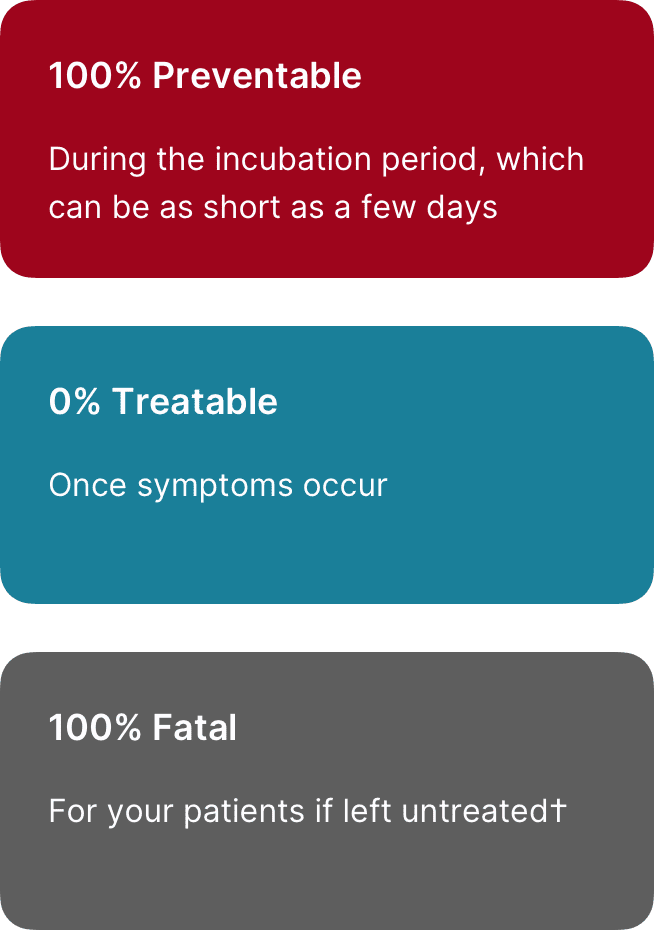

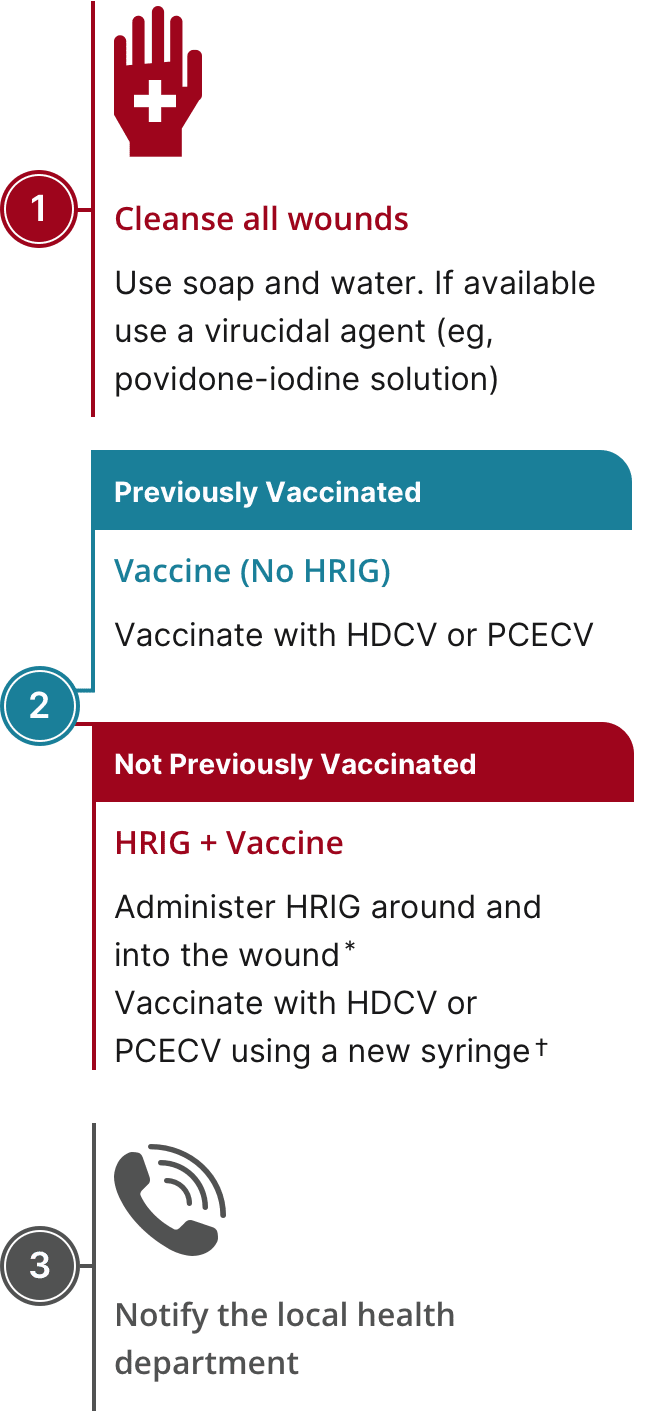

HyperRAB® (rabies immune globulin [human]) is indicated for postexposure prophylaxis, along with rabies vaccine, for all persons suspected of exposure to rabies.

Limitations of Use

Persons who have been previously immunized with rabies vaccine and have a confirmed adequate rabies antibody titer should receive only vaccine.

For unvaccinated persons, the combination of HyperRAB and vaccine is recommended for both bite and nonbite exposures regardless of the time interval between exposure and initiation of postexposure prophylaxis.

Beyond 7 days (after the first vaccine dose), HyperRAB is not indicated since an antibody response to vaccine is presumed to have occurred.

Important Safety Information

For infiltration and intramuscular use only.

Severe hypersensitivity reactions may occur with HyperRAB. Patients with a history of prior systemic allergic reactions to human immunoglobulin preparations are at a greater risk of developing severe hypersensitivity and anaphylactic reactions. Have epinephrine available for treatment of acute allergic symptoms, should they occur.

HyperRAB is made from human blood and may carry a risk of transmitting infectious agents, eg, viruses, the variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) agent, and, theoretically, the Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) agent.

The most common adverse reactions in >5% of subjects during clinical trials were injection-site pain, headache, injection-site nodule, abdominal pain, diarrhea, flatulence, nasal congestion, and oropharyngeal pain.

Do not administer repeated doses of HyperRAB once vaccine treatment has been initiated as this could prevent the full expression of active immunity expected from the rabies vaccine.

Other antibodies in the HyperRAB preparation may interfere with the response to live vaccines such as measles, mumps, polio, or rubella. Defer immunization with live vaccines for 4 months after HyperRAB administration.

Please see full Prescribing Information for HyperRAB.

You are encouraged to report negative side effects of prescription drugs to the FDA. Visit www.fda.gov/medwatch or call 1-800-FDA-1088.